Luca Lapini, Angelo Leandro Dreon & Luca Dorigo

dr Luca Lapini, via dei monti 21, I 33034 Fagagna, Udine, Italy lucalapini1@gmail.com

dr Angelo Leandro Dreon, via della pace 22, I 33080 Frisanco, Pordenone, Italy leandro.dreon@libero.it

dr Luca Dorigo, Zoology Section of Friulian Natural History Museum, Via C. Gradenigo-Sabbadini 22-32, I 33100 Udine luca.dorigo@comune.udine.it

Remarks on the body size of the wildcats (Felis s. silvestris Schreber, 1777) from north-eastern Italy

Abstract: after a descriptive biometric characterization of the wildcats from north-eastern Italy, the AA indicate some new Italian size records for Felis s. silvestris. The big size of the wildcats from south-eastern Alps within Italian populations could be due both to Bergmann’s rule, to their genetic affinity with Balkan populations and to the peculiar prey availability of these fresh and rainy mountain environments, due to frequent small mammal pullulations.

Key words: Wildcat, Felis s. silvestris, Biometric characterization, Size records, North-eastern Italy, small mammal pullulations

Osservazioni sulla taglia dei gatti selvatici (Felis s. silvestris Schreber, 1777) dell’Italia nord-orientale

Riassunto breve: dopo una caratterizzazione biometrica descrittiva dei gatti selvatici dell’Italia nord-orientale, gli AA indicano alcuni nuovi record dimensionali raggiunti da Felis s. silvestris in Italia. La grande taglia dei gatti selvatici delle Alpi sud-orientali nell’ambito delle popolazioni italiane potrebbe essere contemporaneamente dovuta alla regola di Bergmann, alla loro affinità genetica con le popolazioni balcaniche e alla particolare disponibilità di prede di questi freschi e piovosi habitat montani, dovuta a frequenti pullulazioni di piccoli mammiferi.

Parole chiave: Gatto selvatico, Felis s. silvestris, Caratterizzazione biometrica, Record dimensionali, Italia nord-orientale, pullulazioni di piccoli mammiferi

Introduction

The European wildcat is the only authochtonous small cat of temperate forest in European ecosystems.

The low values of genetic distance between five Eurasian and African races of Felis silvestris support the subspecific nominal rank of the European wildcat (Driscoll et al., 2007), but its taxonomic rank is still debated, floating between Felis s. silvestris (European subspecies of a widely distributed politypic taxon: Driscoll et al., 2007; Macdonald et al., 2010) and Felis silvestris (Endemic European species: Gentry et al., 2004; Kitchener et al., 2017).

Even considering the wide species concept suggested by Minelli (2024), only the taxonomic proposal of Driscoll et al. (2007) is supported by both biogeographic and genetic data (Yamaguchi et al., 2015). In our opinion this position represents the better definition of the taxonomic rank of the European wildcat, according to the biological species concept.

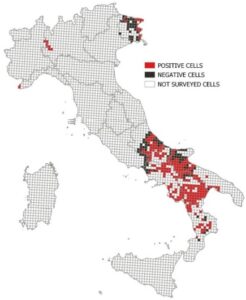

In Italy Felis s. silvestris seems to be quite compartmentalized from a populational point of view. Its Italian populations, indeed, can be subdivided in at least four different genetic groups, that reflect their recent Pleistocenic bio-geographic history (Mattucci et al., 2013).

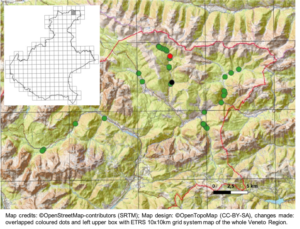

The north-eastern group (1): Friuli Venezia Giulia region, nowaday probably extended to Veneto and Trentino-Alto Adige (Spada et al., 2022: fig. 4); the peninsular Apennines group (2), splitted into two sub-populations distributed on the eastern (2a: Apennines and hills) and western side of the Apennines ridge (2b: Maremma hills and lowlands, probably due to the recent re-colonization of these zones); the Sicilian group (3): restricted to Sicily (Mattucci et al., 2013).

A fifth group it is probably forming also in north-western Italy (Piedmont and Liguria: Spada et al., 2022) -where the species was exterminated between 1950s and 1970s- thanks to wildcats naturally coming from France (Gavagnin et al, 2018).

At present all these Italian sub-populations shown clear trends to expansion, thanks to various Protection Laws (National Law 157/92; Habitat Directive 92/43 CEE; DPR 357/77) and to the impressive increase of the wood cover of Apennines and Alpine mountain Chain occurred in the last sixty years.

In north-eastern Italy Felis s. silvestris has been widely studied (Lapini, 2006 for a synthesis), both from a genetic (Mattucci et al., 2013) and phenetic point of view (Ragni et al., 1989), but its biometric characterization seems to be still provisional.

The present paper intends to delve deeper into this topic.

Methods

The studies on Felis s. silvestris in north-eastern Italy started in the first 1970s, first on the basis of cinegetic sampling (Calligaris et al., 1976), after in the 1980s -stimulated by B. Ragni (Ragni et al., 1989)- to study and enrich the collections of various Natural History Museum from north-eastern Italy (Lapini, 1988, 1989), in legal and logistic cooperation with various Regional and Provincial Public Administrations (Udine, Pordenone, Gorizia, Trieste, Venice, Trento).

The studied samples described in tab. I were collected between 1983 and 2024 mainly in Friuli Venezia Giulia Authonomous Region (north-eastern Italy), mostly thank to road mortality and other occasional samplings.

They were mostly determined by both phenetics (Lapini, 1989; Ragni et al., 1989; Lapini, 2006; Cragnolini, 2016) and genetics (Mattucci et al., 2013), sexed, measured and stored in various Natural History Museum collections.

Their standard body measurements have been taken in millimeters, the total weigth in grams, considering only 70 specimens older than eigth months:

-Total weigth: measured to the nearest gram

-Head-body length: measured in a straigth line from the tip of the nose to the dorsal root of the tail

-Tail length: measured from its dorsal root up to the tip (without apical tuft of hair)

-Hind foot length: measured from the heel to the longest finger

-Ear length: measured from its base to the tip, excluding apical tuft of hair

-Rigth and left testicles measurement: measured along their two principal axis, excluding the epididymis

-Gut index: ratio (Cardias-Anus length)/head-body total length, measured in mm (Ragni et al., 1989)

Results

A first provisional descriptive biometric characterization of the wildcats from north-eastern Italy is given in tab. I.

The global trend of these data confirms the conclusion of Ragni et al. (1989), that first have underlined the big size of the wildcats from north-eastern Italy. These clear phenetic indications were than supported by genetics (Mattucci et al., 2013), highlighting a putative affinity between these wildcats and the Balkan ones, later suggested also by data of Urzi et al. (2021).

The Italian size record of Felis s. silvestris was a road-killed full adult male (fig. 1), collected on September, 29th, 2024 by mr L. De Zan along the 251 Regional Road (km 71+300, Google maps coord. 46.19581, 12.53661), Carnic Pre-Alps, Arcola locality, Barcis Municipality, in the regional decentralization entity of the ex Province of Pordenone.

–Body measurements. Total weigth: 7.242 g; Head-body length: 550 mm; Tail length: 380 mm; Hind foot length: 147 mm; Ear length: 73 mm; Gut index 2.8727; rigth testicles measurement: 16×13 mm, left: 15×15 mm; Stomach content: a just weaned yellow necked wood mouse Apodemus flavicollis.

The necroscopic study of the specimen was performed by L. Lapini, L. Dreon, D. Giacomuzzi, S. Paveglio on April, 8th, 2025.

The precedent record known from northeastern Italy was a road-killed young-adult male (fig. 2), collected on November, 24th, 2016 by mr A. Vidoni along a road in locality La Maina (Google maps coord. 46.453261, 12.726498), Carnic Alps, Sauris Municipality, in the regional decentralization entity of the ex Province of Udine.

–Body measurements. Total weigth: 7.149 g; Head-body length: 565 mm; Tail length: 348 mm; Hind foot length: 150 mm; Ear length: 70 mm (plus 7 mm of apical tuft); Gut index 2.805; rigth testicles measurement: 20×14 mm, left: 13×19 mm; Empty stomach, in the gut 5-10 gr of small mammal hairs and Graminaceae leaves.

The necroscopic study of the specimen was performed by L. Lapini, L. Di Giovanni, L. Dorigo, V. Pacorig on April, 6 th, 2017. In the opinion of B. Ragni, informed by phone during the necroscopic study of the sample, this big specimen was the first Italian record of Felis s. silvestris.

These data probably represent the current size-records for Felis s. silvestris in north-eastern Italy (tab. I).

Provisional remarks

In spite of the putative exaggeration of Hainard (1971), that indicated a record of 18 kg for Felis s. silvestris in France, Hemmer (1993) stated that the maximun size in the European wildcat is reached in central-eastern Europe, where Felis s. silvestris surely reached 8.000 g of total weigth (West Carpathians: Sládek et al., 1971; Kratochvil, 1976). This is also the maximum weigth up to now generically indicated for Italian wildcats, that usually are smaller (Ragni, 1981; Ragni et al., 1989; Angelici & Genovesi, 2003).

A provisional comparison of our data (tab. I) with the information up to now available seems to confirm that the wildcats from north-eastern Italy are similar to the Balkan ones, both from a genetic (Mattucci et al, 2013; Urzi et al., 2021) and phenetic point of view (Ragni, 1981; Ragni et al., 1989; Cragnolini, 2016; Kryštufek, 1991).

The wildcats from north-eastern Italy, therefore, are surely the bigger indigenous Felis of the present Italian mammals faunal assemblage (Loy et al., 2019; Lapini, 2022). The two quoted records, indeed, exceed the maximum weigths recorded both for Italian (Ragni, 1981; Angelici & Genovesi, 2003) and Slovenian wildcats (7.100 g: Kryštufek, 1991).

The size of the European wildcats is a matter of debate, since the climatic warming would to be perhaps able to increase the medium weigth of these termophilic carnivores.

In a recent examination of the biometry of European wildcats, anyway, Stefen (2015) indicate possible males maximum weigth of 10 kg, highligthing the fact that the present availability of time-related biometric data is not enough to confirm sure relations between climatic warming and wildcats size.

The big size of the wildcats from north-eastern Italy could be simultaneously due both to Bergmann’s rule (Clauss et al., 2013), to their Balkan genetic affinity (Mattucci et al., 2013; Urzi et al., 2021) and to the small-mammal pullulations recorded on these mountains (Lapini, 2022).

In these fresh and rainy environments, indeed, there are evidences of impressive pullulations of Apodemus flavicollis and Clethrionomys glareolus at least from the first 1990s (Lapini et al., 1996), repeated over time up to the recent pullulation of the spring-summer of 2021 (Lapini, 2022: fig. 3). Lacking long-terms historical data about these phenomena on the Carnic mountain chain, it is no possible to hypothesize correlation between small-mammal pullulations and local or global warming, but it must be underlined that similar demographic oscillations have been recorded also on neighboring Venetian Pre-Alps (Cansiglio Plateau: Mezzavilla, 2014).

Agronomic historical chronicles of XVI century referred to the Carnic Pre-Alps (Lapini, 2022), moreover, refer that the big rodents pullulation of 1563 destroyed two-thirds of the annual harvests, starving the rural mountain population of the whole zone of Tramonti (Carnic Pre-Alps, now in the R. d. e. of the ex Pordenone Province: Zanon, 1767).

South-eastern Alps are so rainy that the tree-line is locally lowered by an average of 200 metres (Morandini, 1979). In this particular ecological conditions small-mammal demographic oscillations seem to be quite frequent, with great impacts on both trophic networks, wildcat populations and on their body fitness too. Global warming will probably increase these poorly studied demographic and ecologic phenomena, as already noted in various carnivore populations from Canada (Krebs et al., 2019).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank mr L. De Zan (Claut, Pordenone) and mr A. Vidoni (Tolmezzo, Udine) for their special interest in the segnalation of road-kills; to M. Bianchi, N. Bressi, M. De Luca, A. Della Vedova, L. Di Giovanni, D. Colombi, M. Cragnolini, U. Fattori, P. Gavagnin, D. Giacomuzzi, P. Glerean, A. Mareschi, F. Mezzavilla, V. Pacorig, S. Paveglio, S. Pecorella, Fa. Perco, Fr. Perco, E. Randi, A. Sforzi, S. Scognamiglio, A. Spada, M. Spighi, P. Zandigiacomo and G. Zufferli for their help in the study of some samples and for various bibliographic tools. A special thougth to B. Ragni (Spoleto, 1946-2018), who started our researches.

References

-Angelici F. M. & Genovesi P., 2003. Gatto selvatico Felis s. silvestris. In: Boitani L., Lovari S. & Vigna Taglianti A., 2003. Fauna d’Italia, Mammalia, Carnivora, Artiodactyla (II Edizione). Calderini ed., Bologna: 207-221.

-Calligaris C., Perco Fa. & Perco Fr., 1976. La gestione del patrimonio faunistico nella provincia di Trieste. In: AA. VV., 1976. Scritti in memoria di Augusto Toschi. Suppl. Ric. Biol. Selv., Bologna: 133-147.

-Clauss M., Dittmann M. T., Müller D. W. H., Meloro C. & Codron D., 2013.Bergmann’s rule in mammals: a cross-species interspecific pattern. Oikos, 122: 1465-1472.

-Cragnolini M., 2016. On the morphology of the European wildcat Felis silvestris silvestris from central Italy, northeastern Italy and central Germany. Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Biologisch-Pharmazeutische Fakultät Institut für Spezielle Zoologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Masterarbeit, Jena: 1-49.

-Driscoll C. A., Menotti-Raymond M., Roca A. L., Hupe K., Johnson W. E., Geffen E., Harley E. H., Delibes M., Pontier D., Kitchener A. C., Yamaguchi N., O’Brien S. J. & Macdonald D. W., 2007. The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication. Science, 317: 519–523. doi:10.1126/science.1139518.

-Gavagnin P., Lapini L., Mattucci F., Mori E. & Sforzi A., 2018. Sulle tracce del gatto selvatico in Piemonte e Liguria: nuove segnalazioni e riflessioni biogeografiche. Giornata ANP (Associazione Naturalistica Piemontese) “gli ambienti naturali del Piemonte”, November 2018, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.29766.11842.

-Gentry A., Clutton-Brock J. & Groves C. P., 2004. The naming of wild animal species and their domestic derivates. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31 (5): 645-651 (DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2003.10.006).

-Hainard R., 1971. Mammifères sauvages d’Europe. I: Insectivores, Chéiroptéres, Carnivores. Delachaux et Niestlé, Neuchatel: 1-324.

-Hemmer H., 1993. Felis silvestris Schreber, 1977 – Wildkatze. In: Stubbe M. & Krapp F. (eds.), 1993. Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas Raubsäuger, Teil II. Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden : 1076–1118.

-Jacob J. & Tkadlec E., 2010. Rodent outbreaks in Europe: dynamics and damage. In: Singleton G. R., Belmain S. R., Brown P. R. & Hardy B. (eds.), 2010. Rodent outbreaks in Europe: dynamics and damage. International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) publ., Los Baños, Philippines: 207-223.

-Jensen T. S., 1982. Seed production and outbreaks of non‐cyclic rodent populations in deciduous forests. Oecologia, 54: 184–192.

-Kitchener A. C., Breitenmoser-Würsten Ch., Eizirik E., Gentry A., Werdelin L., Wilting A., Yamaguchi N., Abramov A. V., Christiansen P., Driscoll C., Duckworth J. W., Johnson W., Luo S.-J., Meijaard E., O’Donoghue P., Sanderson J., Seymour K., Bruford M., Groves C., Hoffmann M., Nowell K., Timmons Z. & Tobe S., 2017. A revised taxonomy of the Felidae. The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN/ SSC Cat Specialist Group. Cat News, Special Issue 11: 1-80.

-Kratochvil Z., 1976. Das Postkranialskelett der Wild – und Hauskatze (Felis silvestris und F. lybica F. catus). Acta Scientiarum Naturalium, Brno, 10 (6): 1-43.

-Krebs J., Boonstra R., Gilbert B. S., Kenney A. J. & Boutin S., 2019. Impact of climate change on the small mammal community of the Yukon boreal forest. Integrative Zoology, 14: 528-541.

-Kryštufek, B., 1991. Sesalci Slovenije. Prirodoslovni muzej slovenije ed., Ljubljiana: 1-294.

-Lapini L., 1988. Catalogo della collezione teriologica del museo friulano di storia naturale. Pubbl. Mus. Fr. St. Nat., 35, Udine: 1-74.

-Lapini L., 1989. Il gatto selvatico nel Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Fauna, Udine, 1: 64-67.

-Lapini L., 2006. Attuale distribuzione del gatto selvatico Felis silvestris silvestris Schreber, 1775 nell’Italia nord-orientale (Mammalia: Felidae). Boll. Mus. civ. St. nat. Venezia, 57: 221-234.

-Lapini L., 2022. Teriofauna dell’Italia Nord-orientale (Mammalia: Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia). Gortania – Botanica, Zoologia, 44 (2022): 89-132.

-Lapini L., dall’Asta A., Dublo L., Spoto M. & Vernier E., 1996. Materiali per una teriofauna dell’Italia nord-orientale (Mammalia, Friuli-Venezia Giulia). Gortania, Atti del Museo Friulano di Storia Naturale, Udine, 17: 149-248.

-Loy A., Aloise G., Ancillotto L., Angelici F. M., Bertolino S., Capizzi D., Castiglia R., Colangelo P., Contoli L., Cozzi B., Fontaneto D., Lapini L., Maio N., Monaco A., Mori E., Nappi A., Podestà M. A., Sarà M., Scandura M., Russo D. & Amori G., 2019. Mammals of Italy, An annotated Checklist. Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy, 30 (2): 87-106.

-Macdonald D. W., Yamaguchi N., Kitchener A. C., Daniels M., Kilshaw K. & Driscoll D., 2010. The Scottish wildcat: On the way to cryptic extinction through hybridisation: past history, present problem, and future conservation. In: Macdonald D.W. and Loveridge A. J. (eds), Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids, 2010. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 471-491.

-Mattucci F., Oliveira R., Bizzarri L., Vercillo F., Anile S., Ragni B., Lapini L., Sforzi A., Alves P. C., Lyons L.A. E Randi E., 2013. Genetic structure of wildcat (Felis silvestris) populations in Italy. Ecology and Evolution, 3 (8): 2443-2458.

-Mezzavilla F., 2014. Il faggio e la fauna. Indagini ecologiche nella riserva naturale biogenetica Campo di Mezzo-Pian Parrocchia, Foresta del Cansiglio. Corpo Forestale dello Stato – Mipaaf (Ministero delle politiche agricole, alimentari e forestali) ed., Rasai di Seren del Grappa (BL): 1-120.

-Minelli A., 2024. Species. Knowl. Org., 51 (2024), No. 1: 38-67.

-Morandini C., 1979 – L’abbassamento dei limiti altimetrici dei fenomeni fisici e biologici in Friuli, con particolare riguardo alle Prealpi Carniche e Giulie, visto nelle sue cause. Boll. Civ. Ist. Cult., Udine,12/16: 3-15.

-Ragni B., 1981. Gatto selvatico. Felis s. silvestris Schreber, 1777. In: Pavan M. (curatore), 1981. Biologia di 22 specie di mammiferi in Italia. Collana Progetto Finalizzato “Promozione della qualità dell’ambiente”, CNR ed., AQ/1/142/164, Roma: 121-127.

-Ragni B., Lapini L. & Perco Fr., 1989. Situazione attuale del gatto selvatico Felis silvestris silvestris e della Lince Lynx lynx nell’area delle Alpi sud-orientali. Biogeographia, 13: 867-901.

-Sforzi A. & Lapini L., 2022. Novel Criteria to evaluate European wildcat observation from Canera traps and other visual material. Hystrix, 33 (2): 202-204

-Sládek J., Mošansky A. & Palashty J., 1971. Variability of external quantitative characteristics of the wildcat. Biol. Bratislava, 26: 411-420.

-Spada A., Fazzi P., Lucchesi M., Lazzeri L., Mori E., Velli E. & Sforzi A., 2022. An update on the Italian distribution of the European wildcat. Poster presented to XII Congresso Italiano di Teriologia (ATit), Cogne, 8-10 giugno 2022.

-Stefen C., 2015. Does the European wildcat (Felis silvestris) show a change in weight and body size with global warming? Folia Zoologica, 64 (1): 65-78.

-Urzi F., Šprem N., Potočnik H., Sindičić M., Konjević D., Ćirović D., Rezić A., Duniš L., Melovski D. & Buzan E., 2021. Population genetic structure of European wildcats inhabiting the area between the Dinaric Alps and the Scardo-Pindic mountains. Sci Rep, 11, 17984. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97401-5

-Zanon A., 1767. Della coltivazione e dell’uso delle patate e d’altre piante commestibili. Appresso Modesto Fenzo ed., Venezia. https://www.byterfly.eu/islandora/object/libria:283331#page/2/mode/2up

-Yamaguchi N., Kitchener A., Driscoll C. & Nussberger B., 2015. Felis silvestris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en

Fig. 1. The Italian size record of Felis s. silvestris: dorsal and lateral view of a road-killed full adult male found by mr L. De Zan (Claut, Pordenone) on September, 29th, 2024 along the 251 Regional Road (km 71+300, Google maps coord. 46.19581, 12.53661), Carnic Pre-Alps, Arcola locality, Barcis Municipality, in the regional decentralization entity of the ex Province of Pordenone. Photo L. Dreon.

Fig. 2. Past Italian size record of Felis s. silvestris: dorsal and lateral view of a road-killed young-adult male collected on November, 24th, 2016 by A. Vidoni along a street near the locality La Maina (Google maps coord. 46.453261, 12.726498), Carnic Alps, Sauris Municipality, in the regional decentralization entity of the ex Province of Udine. Photo L. Lapini.

Fig. 3. Apodemus flavicollis and Clethrionomys glareolus, about 1.000 dead specimens drowned in the waters of the River Arzino during the small mammal pullulation of spring-summer 2021. Locality Pert, near Pielungo (Carnic Pre-Alps, Vito d’Asio, Pordenone), June, 13 th, 2021, photo A. Mareschi (from Lapini, 2022). Small mammal pullulations are cyclic phenomena, variable from area to area, that in Central Europe seem to be connected to the periodic hyper-production of Fagus sylvatica and Picea abies seeds, probably regulated by climatic stress (Jensen, 1982; Jacob & Tkadlec, 2010). In north-eastern Italy the phenomenon is still poorly studied, but a twenty-year series of data have been recently obtained studying the breeding biology of Aegolius funereus on Venetian Pre-Alps (Cansiglio Plateau: Mezzavilla 2014).

Fig. 4. Updated distribution of Felis s. silvestris in Italy according to the ETRS LAEA 1989 10×10 km grid cartographic system, considering both C1 and C2 data (sensu Sforzi & Lapini, 2022), as shown from the Italian Wildcat Project –www.gattoselvatico.it– (Spada et al., 2022). Red dots ( ) indicate the collecting sites of two Italian size records quoted in this paper.

Tab. I. Descriptive body measurements of some wildcats from north-eastern Italy.

Table columns: Municipality, Province; date of collection; sex; TW-Total weigth: measured to the nearest gram; HBL-Head-body length: measured in a straigth line from the tip of the nose to the dorsal root of the tail: TL-Tail length: measured from its dorsal root up to the tip (without apical tuft of hair); HF: Hind foot length: measured from the heel to the longest finger; EL: Ear length: measured from its base to the tip, excluding apical tuft of hair; GI: Gut index: ratio (Cardias-Anus length)/head-body total length, measured in mm.

| Municipality, Province | Date | Sex | TW | HBL | TL | HF | EL | GI |

| San Pietro al Natisone, Udine | Fall 1983 | Male | 4895 | 570 | 320 | 140 | 75 | 2,5438 |

| Cividale del Friuli, Udine | 31/01/1985 | Male | 4798 | 570 | 350 | 140 | 67 | 2,45 |

| Duino-Aurisina, Trieste | 24/02/1985 | Female | 3251 | 490 | 275 | 126 | 68 | 2,6408 |

| Cividale del Friuli, Udine | Spring 1985 | Female | 3070 | 500 | 300 | 122 | 62 | 2,63 |

| Faedis, Udine | End of July 1985 | Male | 2822 | 480 | 480 | 130 | 300 | 2,9 |

| Savogna, Udine | Fall 1985 | Male | 5400 | 570 | 2,3052 | |||

| Attimis, Udine | February 1986 | Male | 4445 | 520 | 295 | 139 | 70 | 3,0384 |

| Stregna, Udine | 15/02/1986 | Male | 2854 | 550 | 345 | 140 | 68 | 2,8818 |

| Trasaghis, Udine | 09/08/1986 | Male | 4609 | 550 | 315 | 143 | 75 | 2,8 |

| Stregna, Udine | 10/12/1987 | Male | 6200 | 570 | 330 | 135 | 2,9122 | |

| Mossa, Gorizia | 03/09/1988 | Male | 1802 | 448 | 300 | 125 | 63 | 2,8125 |

| Remanzacco, Udine | 18/09/1988 | Male | 2209 | 480 | 300 | 135 | 65 | 2,9375 |

| Attimis, Udine | End 12/1988 | Male | 5800 | 535 | 285 | 131 | 60 | 2,5794 |

| Attimis, Udine | November 1988 | Female | 4780 | 505 | 330 | 135 | 65 | 2,6415 |

| Rive d’Arcano, Udine | 03/01/1989 | Male | 2760 | 510 | 280 | 125 | 69 | 2,7254 |

| Mossa, Gorizia | 18/03/1989 | Female | 2655 | 450 | 305 | 130 | 65 | 3,08 |

| Taipana, Udine | 12/05/1989 | Male | 2739 | 500 | 300 | 132 | 68 | 2,168 |

| San Leonardo, Udine | 20/02/1991 | Female | 4410 | |||||

| Lusevera, Udine | 10/10/1991 | Male | 515 | 310 | 136 | 72 | ||

| Prepotto, Udine | 22/04/1994 | Male | 2530 | 580 | 360 | 147 | 72 | 2,8103 |

| Attimis, Udine | 02/11/1994 | Male | 5077 | 550 | 355 | 135 | 75 | 2,9545 |

| Tolmezzo, Udine | 17/05/1995 | Female | 3000 | 510 | 330 | 125 | 68 | 2,9803 |

| Nimis, Udine | 02/08/1995 | Male | 3390 | 550 | 330 | 140 | 75 | 2,6636 |

| Moimacco, Udine | 11/08/1995 | Male | 3220 | 530 | 320 | 130 | 67 | 2,8113 |

| Sauris, Udine | 01/11/1996 | Female | 2512 | 440 | 300 | 128 | 62 | 2,7727 |

| Trieste | 9/12/1996 | Male | 4500 | 565 | 330 | 146 | 66 | 2,4778 |

| Attimis, Udine | 05/01/1997 | Male | 2760 | 470 | 270 | 125 | 60 | 2,9787 |

| Cividale del Friuli, Udine | 02/02/1997 | Female | 1909 | 445 | 260 | 120 | 61 | 2, 8089 |

| Taipana, Udine | 17/02/1998 | Female | 2920 | 490 | 275 | 130 | 65 | 2,5102 |

| Amaro, Udine | 21/10/1998 | Male | 3106 | 490 | 300 | 133 | 68 | 2,9387 |

| Maniago, Pordenone | 02/12/1998 | Female | 2970 | 440 | 290 | 124 | 65 | 2,7 |

| Prepotto, Udine | 19/12/2000 | Male | 4920 | 540 | 330 | 140 | 65 | 2,7037 |

| Trieste | 10/11/2003 | Male | 2900 | 500 | 320 | 135 | 65 | 3,04 |

| Tolmezzo, Udine | 11/03/2004 | Male | 525 | 320 | 139 | 65 | ||

| Montereale Valcellina | 30/03/2004 | Male | 5000 | 590 | 350 | 150 | 71 | 2,6983 |

| Fanna, Pordenone | 27/01/2005 | Male | 3240 | 505 | 340 | 145 | 66 | 2,9188 |

| Forgaria nel Friuli, Udine | 14/04/2005 | Male | 590 | 360 | 146 | 72 | ||

| Staranzano, Gorizia | 29/04/2005 | Female | 4040 | 520 | 290 | 128 | 65 | 2,8076 |

| Gorizia | 02/12/2005 | Male | 3830 | 513 | 330 | 138 | 63 | 2,5925 |

| Amaro, Udine | 12/12/2005 | Male | 4300 | 550 | 340 | 146 | 70 | 2,6181 |

| Tavagnacco, Udine | 21/12/2005 | Male | 580 | 320 | 140 | 67 | ||

| Trasaghis, Udine | 21/01/2006 | Male | 5750 | 560 | 325 | 140 | 70 | 3,0535 |

| Attimis, Udine | 31/01/2006 | Male | 3630 | 520 | 330 | 135 | 67 | 3,057 |

| Caneva, Pordenone | 08/03/2006 | Male | 4190 | 550 | 320 | 140 | 66 | 2,4909 |

| Premariacco, Udine | 02/07/2006 | Male | 3897 | 590 | 343 | 145 | 69 | 2,8983 |

| Grimacco, Udine | 08/10/2006 | Female | 4555 | 490 | 280 | 130 | 64 | 2,8204 |

| Paluzza, Udine | 06/11/2007 | Male | 5750 | 600 | 325 | 145 | 70 | 2,85 |

| Trieste | 18/02/2008 | Male | 3608 | 540 | 320 | 138 | 71 | 2,685 |

| Tolmezzo, Udine | 19/02/2008 | Female | 3305 | 500 | 300 | 130 | 62 | 2,874 |

| Povoletto, Udine | 04/10/2008 | Male | 2628 | 500 | 310 | 143 | 66 | 2,94 |

| Forgaria nel Friuli, Udine | 24/12/2008 | Male | 5226 | 590 | 360 | 150 | 70+5 | 2,703 |

| Moimacco, Udine | 01/02/2009 | Male | 3995 | 530 | 310 | 132 | 70 | 2,98 |

| Pradamano, Udine | 25/03/2009 | Male | 3685 | 560 | 330 | 138 | 61 | 2,482 |

| Cividale del Friuli, Udine | 26/03/2009 | Male | 2525 | 570 | 330 | 139 | 67 | 2,771 |

| Povoletto, Udine | 13/05/2009 | Male | 3158 | 530 | 330 | 138 | 68 | 2,433 |

| Spilimbergo, Pordenone | 13/11/2010 | Male | 555 | 320 | 135 | 65 | 2,918 | |

| Buja, Udine | 21/12/2010 | Male | 5150 | 565 | 330 | 140 | 61 | 2,814 |

| Cavazzo Carnico, Udine | 29/03/2011 | Female | 1721 | 520 | 310 | 130 | 65 | 3,134 |

| Tavagnacco, Udine | 12/02/2013 | Male | 3987 | 500 | 320 | 140 | 70 | 2,78 |

| Cividale del Friuli, Udine | 11/04/2013 | Male | 1950 | 480 | 320 | 138 | 65 | 2,875 |

| Cividale del Friuli, Udine | 17/11/2014 | Male | 4026,5 | 585 | 350 | 147 | 75 | 2,7692 |

| Castions di Strada, Udine | 30/12/2015 | Male | 3661 | 500 | 320 | 128 | 2,88 | |

| Premariacco, Udine | 19/04/2016 | Male | 2636,5 | 500 | 290 | 125 | 60 | 2,86 |

| Sauris, Udine | 24/11/2016 | Male | 7149 | 565 | 348 | 150 | 70+7 | 2,805 |

| Povoletto, Udine | 22/02/2017 | Male | 6370,6 | 580 | 310 | 138 | 65 | 3,0965 |

| Venzone, Udine | 21/11/2017 | Male | 3277 | 515 | 320 | 138 | 70 | 2,718 |

| Magnano in Riviera, Udine | 22/11/2017 | Female | 2348 | 460 | 285 | 123 | 65 | 2,9347 |

| Premariacco, Udine | 20/02/2018 | Female | 1629 | 460 | 320 | 125 | 65+4 | 2,9347 |

| Pradamano, Udine | 28/02/2018 | Male | 3009,5 | 510 | 320 | 134 | 65 | 2,8039 |

| Barcis, Pordenone | 29/09/2024 | Male | 7242 | 550 | 380 | 147 | 73 | 2,8727 |